Read this article in Français Deutsch Italiano Português Español

Are humanoid robots really coming to a construction work site near you?

17 November 2025

Robots have been threatening to take over work on construction sites for the past several years, if various predictions about the industry have been anything to go by.

That’s partly because of the unpredictability of construction sites that make the safe operation of robots alongside human workers but also in large part due to the simple fact that robots are expensive.

But could that be about to change?

There’s a compelling argument for robots on work sites.

An answer to faltering productivity?

Construction productivity rates have only improved 0.4% annually between 2000 and 2022. Between 2020 and 2022, global construction productivity actually fell by 8% according to McKinsey.

The global management consultancy company has now produced a report called Humanoid robots in the construction industry: A future vision.

French nuclear company Orano unveiled the first intelligent humanoid robot to be used in the nuclear sector on 11 November 2025. The firm has partnered with technology giant Capgemini for the launch (Image: Orano/Capgemini/Cover Images)

French nuclear company Orano unveiled the first intelligent humanoid robot to be used in the nuclear sector on 11 November 2025. The firm has partnered with technology giant Capgemini for the launch (Image: Orano/Capgemini/Cover Images)

It acknowledges that humanoid robots are still in the pilot stage but argues they could emerge as a solution to the productivity problem and urges industry leaders to start preparing.

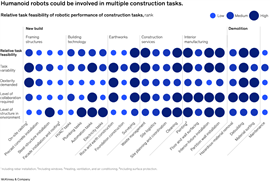

A logical next step to the bricklaying and drilling robots are general-purpose robots equipped with artificial intelligence (AI) that can perform diverse, unrelated tasks across multiple settings alongside humans, it argues.

And large-scale humanoid usage could only be a “a decade away”, it claims, which seems a surprisingly short timescale.

An accelerated timeline thanks to rapid technological advances is a possibility, the report suggests.

The fact that emerging technologies will allow humanoid robots to interpret visual clues and follow spoken instructions “greatly increases their utility”, the report says.

And with further advances in AI models and sensor technology, it forecasts that humanoids could be able to master complex construction tasks by analysing construction videos and demonstrations to learn skills that take humans years to master.

Humanoid robots still have ground to make up

As things stand, humanoid robots can now handle unstructured tasks like lifting irregularly shaped objects but can’t yet cope with more complex activities such as operating small tools with human-level dexterity. Nor can they climb ladders or walk on uneven terrain – at least not yet.

They will also need to advance to the point where they can operate without “fences”, moving freely across sites safely and in collabouration with humans, rather than being confined to certain areas.

Looking at what tasks humanoid robots could perform in ten years or more, it suggested that in a new-build construction projuect, they could assist with on-site casting for framing structures, installing pipes in tight spaces, wire pulling, preparing tools for a human worker, sorting construction waste and cleaning up daily debris, and interior tasks like protecting surfaces before taping, mounting fixed furniture, and holding drywall.

Some of those tasks appear fairly low-tech for such a high-tech solution, especially given that robots currently involve a high capital cost.

Testing McKiney’s assumptions

Construction Briefing contacted McKinsey to understand more about how it arrived its findings and why it has made the forecasts that it has.

Starting with the assertion that large-scale use of humanoid robots could be just a decade away, Susanna Tulokas, associate partner at the company explained what underpinned the assumption.

“Our estimate reflects both rapid technological progress and emerging economic feasibility…As costs decline—from today’s $150,000–$500,000 per unit toward a feasible range of $20,000–$50,000—humanoids could become competitive with human labour,” she told Construction Briefing. “Together, these developments make widespread adoption within the next decade plausible.”

Asked why such a rapid pace of technology adoption could soon be achievable in construction, given that historically it has been rather slow, she added, “Several structural shifts make this moment different. The sector faces an intensifying labour shortage as experienced workers retire and fewer younger people enter the field. At the same time, global demand for housing and infrastructure is set to exceed supply by roughly $40 trillion, creating pressure to boost productivity.”

She also noted that investors are more optimistic about humanoid and general-purpose robots, investing more than $1 billion annually since 2022. “These forces create a stronger business case and urgency for change than in past adoption cycles,” she asserted.

However, she acknowledged that humanoids would have to reach cost parity with local labour before scaling became practical.

To manage investment risk, she suggested first movers pilot partnerships and shape standards, while early adopters can focus on proven, high return-on-investment (ROI) use cases.

“While we have not quantified payback periods in this paper, we emphasise the importance of testing ROI through simulation and pilots,” she said.

While requiring robots to focus on unsophisticated tasks like cleaning up at the end of a day or preparing tools for a human worker may seem like throwing an overengineered solution at a simple task, Tulokas argued that humanoids would need to focus on repetitive, moderately complex activities in a structured environment first due to technical considerations as well as other factors like safety regulations.

Allowing them to demonstrate safety and reliability early on would eventually let them expand into more complex roles that require more dexterity and adaptability as technology matures, she said.

She added, “Safety remains a critical focus. Scaling will require further improvements in collision avoidance, malfunction prevention, cybersecurity, and regulatory standards. However, recent progress in perception models and ‘fenceless’ operations is encouraging. These developments suggest that while safety considerations will shape the pace of rollout, they are not likely to be a fundamental barrier. There are also still regulatory gaps which must be addressed.”

Finally, she forecast that adoption will vary by region. “Areas with higher labour costs and strong productivity incentives are likely to adopt humanoids first, while markets with lower wages or stricter safety regulations - such as parts of Europe - may move more slowly,” said.

Over time, as technology costs fall and global standards evolve, McKinsey predicted that this imbalance will even out.

The presence of humanoid robots in construction sites, then, is not a likely prospect for many parts of the world any time soon. But set a reminder for a decade’s time – whether they’ll be out in force on projects in developed economies where labour supplies are scarce or expensive remains to be seen. And don’t expect to see them climbing a ladder.

STAY CONNECTED

Receive the information you need when you need it through our world-leading magazines, newsletters and daily briefings.

CONNECT WITH THE TEAM