How protected species are reshaping construction delivery

29 July 2025

From mountain passes to offshore wind zones, protected species are increasingly shaping how infrastructure gets built.

A wildlife bridge constructed over a highway. Image: Adobe Stock

A wildlife bridge constructed over a highway. Image: Adobe Stock

With new regulations forcing project teams to plan around threatened habitats, there’s plenty construction should know about endangered species, as their presence often reshapes routes, timelines and building methods.

Here are four species-specific, regional cases where construction and conservation go hand in hand.

1) Bats, newts, & more – United Kingdom

Render of HS2’s “bat tunnel” or the Sheephouse Wood Bat Protection Structure. Image: HS2 Ltd

Render of HS2’s “bat tunnel” or the Sheephouse Wood Bat Protection Structure. Image: HS2 Ltd

UK developers must navigate legal protections for native wildlife such as bats, badgers, dormice and great crested newts. Under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 and Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2017, developers must complete ecological surveys and implement mitigation plans before works proceed.

The Bat Conservation Trust (BCT) recently warned that proposed planning reforms could “cause devastating impacts on our 18 bat species as well as damage irreplaceable habitats.” Kit Stoner, BCT CEO, said, “Removing protections for bats, other wildlife, and habitats will have direct negative impacts on our economy as well as people’s health and wellbeing.”

From a delivery standpoint, such protections have financial and scheduling impacts. Bat surveys remain valid for just one to two years and must be repeated if delays occur. Disturbing a roost or sett without a licence can halt work entirely.

One high-profile case is the £119 million (US$160 million) bat-specific tunnel for the HS2 rail megaproject. The tunnel, under development near Sheephouse Wood, drew criticism over its cost but was deemed necessary to meet legal environmental protections.

An HS2 representative told Construction Briefing, “The demands of the UK planning and environmental consents process come at a high cost, largely out of HS2 Ltd’s control. To comply with laws protecting vulnerable species, including internationally protected bats near Sheephouse Wood, a covered structure over the HS2 line is being built. A range of alternative options were reviewed and rejected on the grounds that they were more expensive or failed to pass the legal test.”

Despite frustrations over delays and red tape, research by The Wildlife Trusts found that bat and newt protection were cited in only 3% of planning appeal decisions, suggesting biodiversity rules are low on the list of what delays construction projects.

2) Koala – Australia

A koala crosses a road. Image: Adobe Stock

A koala crosses a road. Image: Adobe Stock

In Australia, the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) has become a symbol of the tension between infrastructure growth and biodiversity loss.

Following the devastating 2019–2020 bushfires, the species was listed as endangered in parts of Queensland, New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory. Since then, major transport projects in these areas have faced intensified scrutiny and design adjustments.

The Coffs Harbour Bypass in New South Wales, for example, was redesigned to include multiple koala underpasses and more than 30km of exclusion fencing.

The project’s biodiversity report stated, “The design incorporates dedicated fauna crossings and revegetation strategies to maintain corridor connectivity.”

In Queensland, state guidelines now require koala-sensitive design, including fencing standards, offset planting and crossings tailored to their behaviour.

Contractors must account for koala habitat in land clearance timing, route alignment and even revegetation services procurement. Legal challenges and community pushback have already delayed or reshaped projects, making early ecological assessments essential.

3) Snow leopard – Central and South Asia

An endangered snow leopard. Image: Adobe Stock

An endangered snow leopard. Image: Adobe Stock

Dubbed “the ghost of the mountains,” the snow leopard (Panthera uncia) is increasingly vulnerable to habitat loss as countries across Central and South Asia expand road, rail and energy infrastructure through mountainous terrain (many of which are tied to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, with corridors crossing some of the species’ last viable strongholds).

In response, the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and Global Snow Leopard & Ecosystem Protection Program (GSLEP) published guidance in 2025 titled Guiding the Future of Linear Infrastructure Development in Snow Leopard Landscapes.

“Building infrastructure doesn’t have to come at the cost of nature,” said Margaret Kinnaird, WWF’s global lead for wildlife. “We can build smarter; planning and designing with wildlife in mind, like providing crossing structures and avoiding key habitats.”

Recommendations include elevated roads, tunnel segments and realigned corridors; methods used in Europe and North America, but only now entering standard practice in Central Asia.

Across the globe, environmental safeguards are now increasingly written into national review systems and tied directly to multilateral development bank funding. Projects that fail to account for wildlife corridors or habitat disruption risk delays, redesign orders or even withdrawal of financing.

4) North Atlantic right whale – United States and Canada

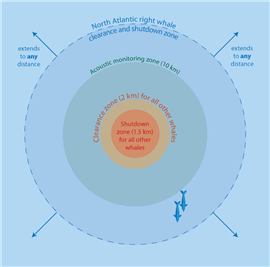

An illustration of Equinor’s whale clearance and shutdown zones. Infrared cameras and passive acoustic monitoring are among the high-tech tools used to ensure whales are not disrupted by offshore construction. Image courtesy Equinor

An illustration of Equinor’s whale clearance and shutdown zones. Infrared cameras and passive acoustic monitoring are among the high-tech tools used to ensure whales are not disrupted by offshore construction. Image courtesy Equinor

With an estimated population of fewer than 360 individuals, the North Atlantic right whale (Eubalaena glacialis) is one of the world’s most endangered marine mammals.

As offshore wind projects ramp up in the US, federal regulations now mandate strict protective measures during construction. These include seasonal restrictions, vessel speed limits, and real-time acoustic monitoring.

According to NOAA, “Reducing sound levels and slowing vessels are two of the most effective ways to reduce the risk of injury or death to these whales.”

Equinor, a developer behind several US offshore wind projects, said in a 2024 environmental statement that it was “committed to implementing all necessary mitigation protocols to minimise potential impacts on marine life, including real-time monitoring and adaptive construction schedules.”

For the Empire Wind project off Long Island, New York, NOAA issued a five-year Incidental Take Authorisation covering construction through 2029. It mandates real-time monitoring and work stoppages when whales are detected. The mitigation strategy includes a pile driving ban from January through April (peak migration season) and daytime-only operations.

Before pile driving begins, trained NOAA-approved observers and hydrophones monitor a 2km clearance zone. If a right whale is seen at any distance, activity halts. Sound field verification buoys track actual underwater noise to ensure compliance.

Equinor told Construction Briefing, “Protective measures are informed by a robust underwater noise management program developed in collaboration with regulatory agencies and experts, and building on other wind farm projects in the US and across the world.”

The firm also supports a continent-wide network of acoustic buoys, deployed with the Wildlife Conservation Society and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, to monitor whale presence.

“This system will help make Equinor better stewards of this lease site,” said Christer af Geijerstam, president of Equinor Wind US.

Construction’s takeaway

Each case reflects a growing trend: endangered species are no longer an afterthought in infrastructure development.

From the Himalayas to the New York Bight, wildlife protection is becoming a formal part of permitting and delivery. With expectations from regulators, lenders and the public, construction firms must treat biodiversity mitigation as part of routine planning and risk management.

As WWF’s Kinnaird put it, “Nature doesn’t have to be sacrificed for progress. With the right approach, we can have both.”

STAY CONNECTED

Receive the information you need when you need it through our world-leading magazines, newsletters and daily briefings.

CONNECT WITH THE TEAM