Read this article in Français Deutsch Italiano Português Español

Why contractor consolidation and public cutbacks drive up US road build costs

11 September 2024

Researchers from the universities of Columbia, California and Yale say that public sector staff cutbacks and a lack of competition among contractors are working to drive up the cost of road repairs across the USA. Lucy Barnard finds out how.

A consolidation in the number of construction contractors and understaffing at state Departments of Transport (DOT) are pushing up the costs of federally funded road building and resurfacing projects across the United States by hundreds of millions of dollars a year new research has claimed.

Zachary Liscow, a professor at Yale Law School led a team of researchers from the universities of Columbia, California and Yale to investigate state spending on road building and repairs across the country on a project-by-project basis.

Road resurfacing work on Seaview Avenue in Palm Beach, Florida in August 2024. Photo: USA Today Network via Reuters

Road resurfacing work on Seaview Avenue in Palm Beach, Florida in August 2024. Photo: USA Today Network via Reuters

They said successive public sector staff cutbacks have been preventing state officials from being able to get the best value for money when auctioning out work to contractors. And, at the same time, they said that a wave of consolidation across the construction industry meant that competition for such auctions was decreasing and contractors were able to force up prices.

In a detailed report comprising a survey of DOT staff from all 50 states, a study of actual project costs, an investigation into procurement practices in each state, and an analysis into the work of individual engineers at one major DOT, Liscow and his team built up a compelling picture exposing the hidden costs to taxpayers associated with dwindling levels of competition in the industry and poorly staffed state transport departments.

The team, which presented its findings to think tank the Brookings Institution in August, built a data set detailing the costs, scope and number of contractors bidding to take on road building and resurfacing projects for each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia, from which they were able to extrapolate each state’s average cost per mile of road built.

They found that some states are spending more than three times as much per mile than others on similar projects.

Moreover, when they correlated the results, they found that states which carried out no bidder outreach spent 17.6% more on project basis – translating to a rise of US$65,000 per mile of road resurfaced and about US$1 million for each project.

Similarly, one fewer bidder on a project was associated with 8.3% higher costs per mile of road – or an increase of US$30,000 per mile.

According to the team’s analysis of the US Census Bureau’s Economic Census for Construction, the number of firms working in the highway, street and bridge construction sector has fallen over the last twenty years.

They said that in the decade to 2017, more than two thirds of states saw the number of main contractors working in the sector decline with the median state losing around 17 roadbuilding firms over that time.

Competition drives costs down

“The role of competition as a cost driver is evident,” Liscow said. “Bidders know the identity and capacity of their competition at the time of bid-letting. DOTs do very little bidder outreach and there are fewer construction firms in most states than there were ten years ago. “

Certainly, there has been a recent flurry of high-profile mergers and acquisitions in the US roadbuilding sector.

In July 2024, Germany’s largest construction group Hochtief and its Spanish parent ACS agreed to merge their north American subsidiaries Flatiron and Dragados, creating the second largest civil engineering construction company in the US.

And a month earlier, Vinci Construction announced it had acquired two family-run public works companies in North America – Newport Construction in New Hampshire and Enterprises Marchand & Frères in Canada. The move follows Vinci’s acquisition of Lane Construction’s roadworks activities in 2018.

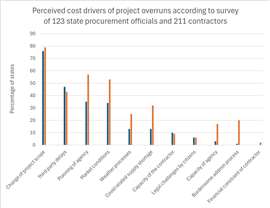

The researchers surveyed 123 state procurement officials and 211 contractors across the country to find out what they thought were the main drivers of road building and resurfacing costs.

Almost 90% of respondents thought that state DOTs were understaffed while more than three quarters said the main reason for cost overruns was a change in the scope of the project.

The team found that state DOTs with the greatest reported problems of staff retention and highest use of consultants were spending 20% more per mile on road building and resurfacing projects than states where this was less of a problem.

The researchers asked 123 state procurement officials (blue) and 211 contractors (orange) what they thought were the main drivers of road building and resurfacing costs. Respondents were free to choose as many answers as they wanted. Source: survey data.

The researchers asked 123 state procurement officials (blue) and 211 contractors (orange) what they thought were the main drivers of road building and resurfacing costs. Respondents were free to choose as many answers as they wanted. Source: survey data.

According to the survey, one of the biggest drivers of cost increases was when officials made frequent change orders to works which were already in progress, with each change working out as an extra US$25,000 per mile of road.

“A lack of capacity at the DOT can hurt the quality of project plans, either from under-staffing in-house or from outsourcing to consultants with limited institutional knowledge and misaligned incentives,” said Liscow. “The lack of specifity in plans introduces risk to the contractor which increases contractor bids and opens up the DOT to a costly and time-consuming renegotiation process when the scope of the project changes.”

Moreover, even after variations in each state’s population density, weather, wage costs etc were taken into account, the team still found a significant correlation between states which were reported to have the highest levels of understaffing and those with the greatest project costs per mile. It calculated that a one standard deviation increase in reported consultant costs is associated with a 19% increase in costs per mile – equating to US$70,000.

The team then analysed the 1,144 road resurfacing projects procured by 139 resident engineers at California Department of Transport, Caltrans to find out how much each project’s resurfacing cost could be attributed to individual engineers.

They found that replacing the worst performing engineers (those in the 95th percentile of the cost distribution) with an average-performing colleague would reduce costs by 5.2% or an average of US$24,000 per mile. And, with most resurfacing projects spanning around nine miles each, the saving translates to US$220,000 per project – or a US$13 million per year saving for Caltrans spread of its usual 60 resurfacing projects per year.

Public sector cutbacks add to project cost inflation

Over the last 20 or 30 years, US state highways departments have often become an easy target for state officials looking to cut costs without trimming from high profile education or law enforcement departments.

According to the US Annual Survey of Public Employment and Payroll which is produced by the Census Bureau, between 1997 and 2020 the number of people employed in state ‘highways’ departments has shrunk by 40,000, a decrease of about 20%.

Total state public sector employment rose over the same period, such that the ‘highways’ share of total state public employment shrunk from over 6% to about 4.5%.

Wage and hiring freezes during the pandemic saw a further haemorrhaging of public sector employees to both the private sector or into early retirement, leaving those remaining with higher workloads.

“We find states where respondents cite consultants as a cost driver have significantly higher costs,” says Liscow. “This is especially striking, given that we are only measuring the cost of the project that is paid to the contractor, not any internal staffing costs to the DOT. Therefore, the increase in costs due to the consultant is not because the consultants bill at a high hourly rate (which can also be true). There are a few mechanisms that can lead contractors to increase costs ex-post. The most frequently cited by industry professionals is a lack of institutional knowledge, which can lead to both mistakes in the project plans and delays when communicating with contractors.”

STAY CONNECTED

Receive the information you need when you need it through our world-leading magazines, newsletters and daily briefings.

CONNECT WITH THE TEAM