Read this article in Français Deutsch Italiano Português Español

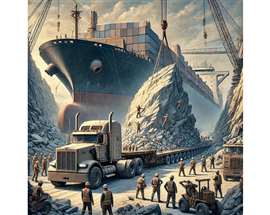

Moving mountains: freight forwarders helping to get the biggest loads from A to B

24 February 2025

Who are the men and women tasked with helping to move some of the world’s largest, heaviest and most awkward objects around the world and what do they actually do? Lucy Barnard speaks to the freight forwarders who specialise in projects to shift unusual and heavy loads

Image created using AI

Image created using AI

Transporting heavy machinery and other similarly large, heavy and awkward objects around the world can be a tricky business and freight forwarders are a key link in the supply chain.

Freight forwarders are the travel agents of the cargo industry – the people working behind the scenes to co-ordinate the complex web of trucks, ships, barges, cranes, warehouses and red tape, all required to get oversize and-or overweight, out of gauge, or otherwise awkward loads from A to B.

As a freight forwarder specializing in arranging the movement of large pieces of construction equipment, Andrew Civil is used to plans going awry. As Civil, general manager at specialist freight forwarder WWL ALS, points out, from bad weather to roadworks to changes in travel permits or weight restrictions, it’s a job where Murphy’s Law firmly applies.

“Anything can happen in this line of work, literally anything. It’s quite bizarre on occasions as to what can impact a job,” Civil says.

What does a freight forwarder do?

Freight forwarders seldom own the transport equipment or cranes used for the moves. Instead, their role is to act as middlemen, working out ways to get things from wherever in the world they are to where they need to go.

Part of that is phoning, emailing, faxing and texting people to book the ships, aircraft, trucks, cranes, barges and transfers needed to get equipment where it needs to be. Part is navigating a path through all the other red tape involved – arranging insurance, permits and completing customs statements. Another part is negotiating solutions to the many bureaucratic and practical obstacles that can delay or prevent deliveries from getting from A to B.

And as Civil points out, that process alone can be extremely time intensive. Before even taking on an abnormal load job, Civil says he and his team research each machine, or whatever else the load is, to check the actual dimensions and weights, often sometimes the largest loads in person before applying for road permits or passage on a ship.

ALS organised the transportation of an absorber for a gigafactory from Asia to the USA. Photo: ALS

ALS organised the transportation of an absorber for a gigafactory from Asia to the USA. Photo: ALS

“We could get given a job at the start of the year, in January, that’s not due to move until April or May but, because of the complexity of the move, we’ll start getting the permissions in place and do as much pre-checking as possible. And will continue to check right up until the job starts,” he says.

“The customer will start making his plans for getting the goods ready to be shipped and you build in time buffers and everything. But even though you’ve got these in place perhaps four to six weeks before you’re going to do the job, something can always happen. A bridge can develop a fault, a weather event, emergency roadworks on that route which means you’re unable to transport or ship the goods. Sometimes it’s not a case of waiting a few hours. Sometimes you have to wait weeks.”

Only a very small number of companies specialize in moving heavy equipment around the world, a type of freight forwarding known in the trade as project cargo or project logistics which, alongside the extra bureaucratic headaches of moving heavy and large loads around the world, can also involve temporarily removing street furniture to allow wide loads to pass, trimming vegetation along the route, and even reinforcing or creating new roads and bridges.

“Project logistics is not about delivering a small parcel from Amazon weighing 1 kg. It is about heavy loads weighing 300 tonnes and the size of a heavy truck or house,” says Ilya Goncharov, head of industrial projects at Denmark-headquartered 3PL Group.

“Even in the world of freight forwarding companies there are not many people willing to take responsibility for the delivery of a project cargo with a minimum of 8 to 10 different suppliers all the way from A to B with hundreds of hours planning in all stages without any guarantees to avoid extra costs, demurrage [late fees for ships], or damage.”

3PL Group transports a 19,000kg telescopic access bridge. Photo: 3PL

3PL Group transports a 19,000kg telescopic access bridge. Photo: 3PL

Project report

Goncharov points to one of his firm’s recent jobs to transport an access bridge for an offshore oil platform from the Netherlands to the UAE via Belgium.

The project involved removing a 19 tonne telescopic access bridge measuring 14.5 metres high, 2.74 metres wide and 3.36 metres long from its position in the Dutch waters of the North Sea.

The bridge was then loaded onto a lowbed semi-trailer and driven to Antwerp in Belgium before being loaded onto a roll trailer and secured for sea transport, before then being shipped to Jebel Ali Port in Dubai.

As part of the project, 3PL Group was also responsible for obtaining correct customs documentation and clearance as well as all handling and port operations in Antwerp.

“The people who take responsibility for project logistics are the master chefs of world logistics,” says Goncharov. “They are people with outstanding abilities and one of the most important partners for your business.”

“What if your cargo is worth US$100,000,000 and the authorities refuse to grant a permit for your truck at the last minute? Suddenly you need to reschedule the delivery and explore an alternative route. What if there is a storm in the port for a week, covid, wars, sanctions? You can end up facing ship demurrage costs of $50,000 per day.”

For the most part, freight forwarders charge a percentage of the total cost of the shipment – a cost which is ultimately borne by the customer.

Blanca Claeyssens is managing director at ASA France, a company specializing in advising freight forwarders and customers on transporting loads which are typically worth millions of Euros. She says her firm charges a rate which equates to either 5 per cent of the transport cost or 0.5 % of the project cost.

Reducing overall costs

“In the end using our company does not bring costs, it reduces cost,” she says. “We save money by taking certain decisions upfront because you don’t have to live with the consequences afterwards which are often much more costly than the investment in us.”

Claeyssens points to a project the company undertook to help transport three huge gas tanks manufactured in Poland to a remote lagoon in Tahiti, in the South Seas.

“To ship the tanks the customer needed a vessel in the Port of Tahiti which would have required bringing in the sort of barge which you would normally only find in larger markets like Europe and which would easily have cost €1 million,” she says.

“There was a little barge working between the islands but nobody knew if it could be used or not. We did a feasibility study to see if it could be used and we found out that it was good so in the end the client paid just €36,000 to use the barge instead of €1 million.”

ASA France helped transport gas tanks by barge in Tahiti. Photo: ASA France

ASA France helped transport gas tanks by barge in Tahiti. Photo: ASA France

Other examples, she says include working on student housing modules manufactured in Morocco for use in the UK.

“The architects had a lot of fun creating these buildings because they started from scratch. But to move it was a logistical nightmare,” Claeyssens says.

“On the interior there was already a mirror and the bed and everything was in there, so it was really fragile. It had to be lifted straight up or everything on the inside would be broken. So we ended up creating a lifting beam and we created really simple colour-coded instructions for the stevedores at the port to use.”

Competiton heats up

While those involved in transporting construction equipment and other heavy loads around the world emphasise the personal service and high levels of skill required for each job, companies are coming under greater pressure to compete in an increasingly crowded marketplace.

“We’re quite a specialist company but what we’ve found, probably since the last recession is that there are more companies out there offering similar services to us,” says Civil. “The market has got far more competitive in terms of suppliers and I think digitalisation is going to become more important.”

Despite still being seen as an industry in thrall to paperwork, many freight forwarding companies have been shifting their operations online.

This is partly in response to a spate of freight-tech start-ups such as Freightos, Magaya and Flexport which have been promising to disrupt the mainstream market by automating supply chain processes traditionally done manually.

The vision behind such tech is that better internet connectivity on ships is simplifying tracking cargo in real time, making it easier to better manage connections and redirect goods if a problem occurs. Companies like Uber Freight and Amazon Flex are already attempting to match spare capacity with mass market cargo that needs to be shipped.

“Amazon, Netflix and Uber have trained us to expect instant updates, seamless experiences and personalised solutions in our daily lives. The same mindset is now transforming the logistics industry,” says Danya Rielly, director of digital marketing at Magaya Corporation. “Shippers demand real-time visibility, transparency and seamless collaboration. For freight forwarders and other logistics service providers, meeting these expectations isn’t optional, it’s essential.”

Freight-tech startup Magaya is attempting to disrupt the market. Image: Magaya

Freight-tech startup Magaya is attempting to disrupt the market. Image: Magaya

According to a November 2024 survey of 71 freight forwarders and logistics service providers by research firm Adelante and sponsored by Magaya, shipment booking and scheduling tasks were given the highest priority for digitalisation, followed by warehouse and inventory management.

Project logistics firms say they have already made great strides in digitising many of their processes.

“Our industry has seen many great digital changes in the last 10 to 15 years,” says Ilya Goncharov. “Full electronic document management, electronic permits for heavy vehicles, bills of lading and invoices,” he explains. “We have great online platforms and digital tools that simplify our documentation, tracking and communication.”

Even so, progress has been uneven. The Adelante survey found that just 23 % of freight forwarders have digitised the majority of their overall business processes while 14 % said they had digitised less than a tenth of their business.

Much of this is to do with institutional red tape. If local authorities will only issue transport permits via fax, then companies have little incentive to digitise the process. Similarly, the fragmented nature of the industry makes it difficult to integrate the many different processes and systems of trucking and shipping companies providing visibility on a shipment’s current location.

Moreover, Goncharov says that for the largest and most unusual cargos which require companies to build new roads or bridges or to engineer new methods for handling the cargo, automation is simply not an option.

“Project logistics has not become an oversized Uber. Many have tried to do this but to no avail,” he says. “There are too many important intermediate stages that are not connected with each other. You are literally assembling a mosaic or a construction set for which you yourself make the parts.”

“You still cannot order a 100 tonne modular structure delivery for your Arctic gas plant in one click – it is not a pizza.”

STAY CONNECTED

Receive the information you need when you need it through our world-leading magazines, newsletters and daily briefings.

CONNECT WITH THE TEAM