Is China’s Belt and Road Initiative stumbling amid debt problems?

29 March 2023

The Maputo-Katembe bridge in Mozambique, the longest suspension bridge on the African continent, was built under China’s Belt and Road initiative (Image: Malajscy via AdobeStock - stock.adobe.com)

The Maputo-Katembe bridge in Mozambique, the longest suspension bridge on the African continent, was built under China’s Belt and Road initiative (Image: Malajscy via AdobeStock - stock.adobe.com)

China is pivoting away from investment in new infrastructure projects beyond its borders under the multi-billion-dollar Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

That’s according to a new report, which has found that China is increasingly having to switch to be a lender of resort for developing nations struggling to repay their BRI debts.

The study by AidData, the World Bank, the Harvard Kennedy School, and the Kiel Institute for the World Economy found that China had undertaken 128 rescue loan operations across 22 debtor countries worth US$240 billion by the end of 2021.

The 22 countries across which China’s rescue lending efforts are spread include: Argentina, Ecuador, Suriname and Venezuela in Latin America; Angola, Sudan, South Sudan, Tanzania and Kenya in Africa; Turkey, Oman and Egypt in the Middle East; and Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Mongolia and Laos in Asia.

China has already responded to the financial distress of several debtor countries by reducing new overseas lending to the global south.

A separate report which emerged earlier this year, by the Green Finance & Development Centre (GFDC), part of the Fanhai International School of Finance in Shanghai, noted a “significant slump” in Chinese BRI engagement in sub-Saharan African countries in 2022.

Nonetheless, other regions saw strong increases. Investments in East Asia rose 151% in 2022, with a 76% rise in construction contracts, for example. Investment in Middle Eastern countries has also expanded.

The GFDC report also suggested that a rebound in BRI engagement is “possible” in 2023, with a focus on electric vehicle battery plants, pipelines and roads, data centres, resource-backed deals like mining and oil, or high-visibility projects like railways.

Bailout grows

Nonetheless, the new AidData and World Bank study noted that the scale of China’s global bailout lending programme has grown rapidly, largely behind the scenes.

It found that China has extended more than US$185 billion USD in the past five years alone (2016-2021) to countries struggling with debt.

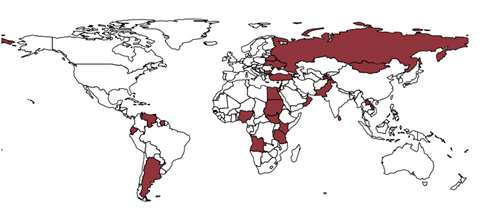

The geography of China’s bilateral bailouts: Countries marked in red have received rescue lending from China. Source: ‘China as an international lender of last resort’ (AidData 2023)

The geography of China’s bilateral bailouts: Countries marked in red have received rescue lending from China. Source: ‘China as an international lender of last resort’ (AidData 2023)

“Almost all Chinese rescue loans have gone to low- and middle-income BRI countries with significant debts outstanding to Chinese banks,” the report said.

It asserted, “China has developed a system of ‘Bailouts on the Belt and Road’ that helps recipient countries to avoid default and continue servicing their BRI debts, at least in the short run.”

The emerging global superpower has extended the loans to debtor countries either directly from state-owned Chinese banks, or through a “swap line” facility where the yuan is disbursed by China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China, in return for domestic currency.

The report said the repeated bailouts by China are reminiscent of the “serial lending” practices by the IMF in recent decades and the serial restructurings and bridge credits by private creditors prevalent during the 1980s debt crisis.

And it noted, “A common characteristic of the recipient countries of Chinese rescue lending is that they have borrowed extensively from Chinese banks during the lending boom of the 2010s.”

The report concluded, “We show that China’s role as an international crisis manager has grown exponentially in recent years following its long boom in overseas lending. Its position is still far from rivalling that of the United States or the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which are at the centre of today’s international financial and monetary system and the effectiveness of its rescue lending operations is not well understood. However, we see historical parallels to the era when the US started its rise as a global financial power, especially in the 1930s and after World War 2.

“China has demonstrated that a major creditor country…can create a large system of cross-border rescue lending to nearly two dozen recipient countries, while at the same time keeping its bailout operations largely out of public sight. Much more research is needed to measure the impacts of China’s rescue loans.”

China has been outspending rivals

Since the BRI was introduced in 2013, China has been significantly outspending its overseas rivals, a previous AidData report found.

In an average year, China spent US$85 billion on its overseas development programme in an average during the BRI era, compared to the US’s $37 billion. Its support has largely taken the form of debt rather than grants, with a 31-to1 ratio of loans to grants.

But with the financing of bigger projects has come a greater level of risks.

An Overseas Development Institute (ODI) report found that more than 15 projects, worth a combined US$2.4 billion experienced financial problems in 2020.

In January this year, Uganda cancelled a US$2.3 billion deal with China Harbour Engineering to build a major new railway line linking Kampala and Uganda’s border with Kenya. The move came after Beijing decided not to fund the 273km line via its Export-Import Bank amid concerns about its financial viability.

Meanwhile, a BRI joint venture between a Chinese consortium and four Indonesian state-owned businesses to build a high-speed rail project between Jakarta and Bandung is running three years behind schedule and over budget. The cost of the project has risen from US$6 billion to nearly US$8 billion, according to reports. Although Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo and China’s President Xi Jinping have jointly said that they remain committed to it.

And in Pakistan, authorities cracked down on protests from local workers’ rights movements in the town of Gwadar, home to a Chinese-built port, amid complaints that local people have not benefited from the $50 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Pakistan is estimated to owe nearly one-third of its foreign debt to China and several BRI projects in the country are reported to have stalled.

STAY CONNECTED

Receive the information you need when you need it through our world-leading magazines, newsletters and daily briefings.

CONNECT WITH THE TEAM