How construction workers are struggling with poor mental health

16 August 2021

Construction workers around the world are far more likely to die by their own hand than to be killed in an accident on site. But what is being done help prevent the thousands of suicides which take place every year in the construction industry and is it enough? Lucy Barnard finds out.

For construction worker Andy Stevens, the final straw came when his marriage was breaking up and he was thrown out of the family home.

The self-employed builder and father of two from Surrey in the UK attempted to take his own life with a kitchen knife when confronted with a barrage of problems at work and at home, exacerbated the post traumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety caused by physical abuse suffered in childhood.

Builders in Malmo, Sweden, by Timmy_L on flickr

Builders in Malmo, Sweden, by Timmy_L on flickr

“I was sitting in a house where I was sort-of living at the time. I must have gone into some sort of haze. I was suffering badly,” he says.

“I must have called a number but I don’t know to this day which one. The ambulance people managed to get there just in time. They said I was sitting there with a kitchen knife. The next thing I knew I was waking up in hospital with the mental health team around me.”

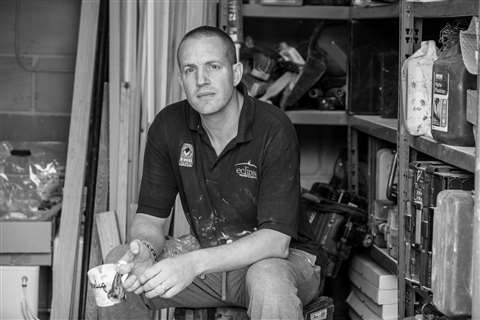

Now 45, Stevens runs his own small building firm, Eclipse Property Consultants, which specializes in extensions and new builds. He also works as a broadcaster and acts as an ambassador for the Lighthouse Club - a UK-based construction industry charity that provides financial and emotional support to construction workers dealing with mental and other health issues.

“This is a massive problem in the construction industry,” Stevens says. “It’s happened to mates of mine. You hear about it all the time. Recently three scaffolders jumped at a construction site in South London. One of them was only nineteen years old.”

Suicide rates in construction

Poor mental health is the biggest cause of death in the construction industry. According to the Office for National Statistics more than 1,400 construction workers committed suicide in the UK between 2011 and 2017 – more than three times the national average for men.

By comparison, last year there were just 30 fatalities caused by accidents on building sites nationally.

Andy Stevens - picture courtesy of Andy Stevens

Andy Stevens - picture courtesy of Andy Stevens

And, for UK construction workers, things appear to be getting worse.

Research by Glasgow Caledonian University and the Lighthouse Club found that the number of suicides per 100,000 for construction workers rose from 26 to 29 in the four years to 2019.

And for unskilled workers, such as labourers, the number rose from 48 to just over 73 suicides per 100,000. This compares with a suicide rate of around 10.4 per 100,000 amongst men in 2018.

“It’s often the trades like scaffolding, bricklaying and groundworkers. Some go to work to escape troubles in their home lives then you get pressure from your boss and the whole thing snowballs out of control,” Stevens says. “Your mind races when you’re on your tod and you close up rather than talk to anyone.”

“When you run a small building firm it’s very hard when you get knocked,” Stevens says. “If you get your van nicked [stolen] or your tools nicked it’s exceptionally tough.

“Being self-employed can be really hard. Things like how to run a business, payment schedules, contracts, how to price a job, etc. These are all ‘suck it and see’ type things which can be very stressful.”

And it’s not just construction workers in the UK who are suffering. Countries around the world are reporting similar trends.

Why mental health should be a priority in the construction sector

In the USA, the Centre for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) reported that in 2018 there were 1,008 construction fatalities but 5,242 suicides by construction workers that year, equating to a rate of 45.3 per 100,000. This compares with an average male suicide rate of 27.4 per 100,000.

“I’ve been in the industry for well over 35 years working on projects, but I never thought about mental health,” says Greg Sizemore, vice president of health, safety, environment and workforce development at Associated Builders and Contractors (ABC).

“These figures revealed something important that should be a priority for every person in the industry to address.

“Our industry has done a great job in reducing safety incidents on site. We’ve made great strides in improving the physical health of employees. But we need to blend that with improving mental health and focus more on total human health.

“We want to look at the person wearing the hard hat,” says Sizemore.

How cultural norms and expectations contribute to suicidal behaviour

“When I started up in business in the 1970s no one ever asked me how I felt. I was expected to leave all my concerns in the front seat of my pickup truck,” Sizemore adds. “But now we know that that is simply not realistic.”

Sizemore says that one of the key reasons why suicide rates in the construction industry remain so high is the industry’s macho culture.

“We’re a tough guy crowd. We’re stoic,” he says. “Ours is not a talkative culture. We have a typical suck it up mentality.”

Key factors affecting mental health

In addition to a lack of open communication and the pressure of cultural expectations, other key factors include the fact that construction workers often end up working long hours in temporary accommodation far away from family and friends.

The unpredictable nature of the work and isolation can leave them more susceptible to relationship problems, debt, addiction, legal problems and cyber bullying.

Sizemore adds that the US construction industry often acts as a bridge for veterans coming out of the military, some of whom are already suffering from severe post-traumatic mental health issues.

“We have an aged industry with more people staying in the workplace longer and they are often processing chronic pain and finding coping mechanisms, be that alcohol or illegal substances. That can quickly become a raging addiction that pushes someone over the edge,” he says.

Similar figures can be found in Ireland, where figures by the Construction Industry Federation found that men working in the construction and production industries accounted for nearly half of all male deaths by suicide.

Maria Åberg, assistant professor of public health and community medicine at the University of Gothenberg, is currently carrying out research into suicide rates in the Swedish construction industry.

Causes of mental illness in construction workers

Åberg and her team sent a questionnaire to 420 construction workers in spring 2021 asking them about their working conditions. She says that initial findings show that between 12 and 17% of those who responded showed signs of mental illness.

“In recent years, the construction industry in Sweden has experienced an increase in mental illness at work,” she says. “Poor mental health is a problem in the construction industry in Sweden because of stress and lack of recovery time.

“Other problems are poor leadership, conflicts at work and a lack of confirmation and appreciation from line managers. There are also concerns about the physical work environment.”

In Germany, which prides itself on its comprehensive and historic workers compensation system, concern is growing over the role deadline pressure is playing in construction workers’ mental health.

“Employees in the construction industry perceive an increasing pressure to meet deadlines, a heightened workload and excessive demands,” says Frank Werner, deputy director of prevention at Berufsgennosenschaft der Bauwirtschaft (BG BAU), the insurance association for the construction industry. “The absenteeism attributable to mental stress are on the rise and cause long periods of absence.”

However, he adds that although the Federal Statistics Office keeps information on suicides, little work has been done so far to discover whether construction workers are particularly affected.

How we can reduce construction worker suicide

Australia is one of the countries leading the way in researching construction industry suicide.

Australian construction industry charity Mates In Construction analysed dozens of coroners reports to identify the common factors which had pushed men in construction over the edge.

It found that these included job insecurity, transient working conditions, issues connected to business and financial management and fear of legal prosecution.

Substance abuse, alcohol use and mental health issues were also prominent factors alongside family breakdown and the lack of access to children.

How on site training can help suicidal employees

The charity, which was founded in 2008 with the aim of reducing suicide rates in the Australian state of Queensland, provides a programme of on-site suicide prevention training to workers in the construction industry in order to help them notice changes in their co-workers’ behaviour and to encourage and support those in crisis to seek help.

Since then the charity has trained more than 230,000 workers across more than 1,000 sites. The charity has also recently expanded to New Zealand.

Are suicide prevention programmes effective?

A 2020 report by MIC and Melbourne University found that, since the programme has been introduced, suicide rates among construction workers across Australia have declined by almost 8%, bringing the level closer to the male average in many Australian states.

“When Mates was started in 2008, suicide was seen almost entirely as a health problem requiring health responses,” says Mates in Construction CEO, Chris Lockwood. “Programmes such as Mates have shown that we achieve much more when we engage all of the community.”

In the UK too, a number of charities and organisations are working to support construction workers who are in crisis.

The Lighthouse Club, a charity which has been providing help and support to construction workers in the UK since 1956, also runs and staffs the Construction Industry Helpline in the UK and Ireland, has helped to establish a Building Mental Health online portal to help companies develop a positive mental health culture.

Like a number of organisations around the world, the charity offers mental health first aider courses aimed at training construction workers to support colleagues who are struggling.

So far it has trained more than 284 mental health first aid instructors who have delivered 3,349 mental health awareness courses and have trained over 5,000 front line mental health first aiders.

The result of this effort mean that the construction industry now has the highest number of Mental Health First Aid Instructors of any similar industry.

Why are construction worker suicides still rising?

But Bill Hill, Lighthouse Club chief executive, says that despite this effort, the latest research shows that construction suicides in the UK continue to rise.

“It could be that our messages are getting through to the white collar workers, but we’re simply not reaching our ‘boots on the ground’ workforce,” he says.

“Or it could be that that as 53% of our workforce are self employed, agency or zero-hour contractors the socio economic pressures are greater and message isn’t getting down the supply chain.”

“The focus has to be on pulling together collectively and investing in more pro-active resources to ensure that the situation does not continue to decline,” he adds.

“We need to look at different interventions for different occupational groups. What might work for a site manager may not be relevant for a bricklayer.”

Mates in Mind, a charity established in 2016 with support from the British Safety Council, also offers mental health training to the UK industry.

It has built a community of more than 185 supporter organisations, reaching more than 187,000 individuals across the sector.

Suicide prevention in the US

Back in the US, ABC’s Sizemore says that construction organisations are attempting to implement strategies that have been shown to work in both Australia and the UK.

Working together with fellow industry body, the Construction Industry Alliance, ABC recently launched its own www.preventconstructionsuicide.com website.

It offers online and offline training and invites construction companies to take a pledge to stand up for suicide awareness and advises incorporating suicide awareness into existing “toolbox” safety talks.

“It’s the tip of the iceberg but we need to create the kind of narrative where colleagues are able to say you’re just not here today, is everything ok? We need to equip and empower to make a difference,” Sizemore says.

“We have some very successful contractors who do things very well but the vast majority of construction firms in the USA are small shops of 25-50 employees with no human resources platform and one person running accounts and personnel.

“It’s small business America. We’re pushing resources out there to help them understand what to do,” he adds.

For Sizemore, the key thing is to persuade US construction companies to commit to change.

“It’s important to have management fully on board from the C-suite [executive level] downwards so we can really get the message out to people. If we can get the highest ranking official engaging then three quarters of the battle is won,” he says.

“It doesn’t matter if the workforce is 50,000 or five, the leadership must commit to change the culture by putting systems and processes in place. It’s how to communicate to employees that its ok to have that conversation.”

Suicide prevention strategies

In Sweden too, Åberg says that industry bodies are just starting to work towards implementing their own suicide prevention strategy after collaborating with Mates in Construction with research.

“Our proposed study will utilize both quantitative and qualitative methods to increase our understanding of how work-related exposures are related to suicide risk in men,” she says.

“Findings from the present project might guide an intervention strategy to decrease premature death by suicide among construction workers.”

“More could be done,” she says. “New knowledge is needed as an important step on the way to developing a better understanding of modifiable risk factors and possible preventive measures for suicidal behavior in the construction industry.”

Back in the UK, Andy Stevens is evangelical in his efforts to spread the word about mental health awareness and to persuade construction workers to open up.

“I’m a 6 ft 3, an ex-rugby player with a face like a kicked-in biscuit tin – I’m not the sort of person you expect to stand up and talk about this,” he says.

“But if one person working in construction can take something from this, then it’ll help.”

Who to call in a crisis

The Lighthouse Club provides financial or wellbeing support in th UK and Ireland - call their 24/7 confidential Construction Industry Helpline for help now on 0345 605 1956 in the UK, and 1800 939 122 in Ireland.

Mates In Construction offers a free, confidential helpline in Australia available 24/7 on 1300 642 111 or 0800 111 315 in New Zealand.

The Construction Industry Alliance for Suicide Prevention refers those in crisis to The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline in the US which provides immediate help on 1-800-273-TALK (8255)

STAY CONNECTED

Receive the information you need when you need it through our world-leading magazines, newsletters and daily briefings.

CONNECT WITH THE TEAM